Episode 171 – Zwangendaba’s Exodus from Pongola to Lake Tanganyika and the Story of the Ngoni

Welcome back to another deep dive into the history of South Africa. In this episode, we’ll explore the incredible journey of Zwangendaba and his people from the early 1800s until 1848. This episode takes us beyond the Limpopo and Motloutse Rivers, into a contested land of sapping heat and dramatic migrations.

The Aftermath of the Seventh Frontier War

After the British extended their control over the Ceded Territories post-Seventh Frontier War, our focus shifts back to the north. This region witnessed a series of significant events and migrations that reshaped southern Africa.

Zwangendaba and the Ngoni People

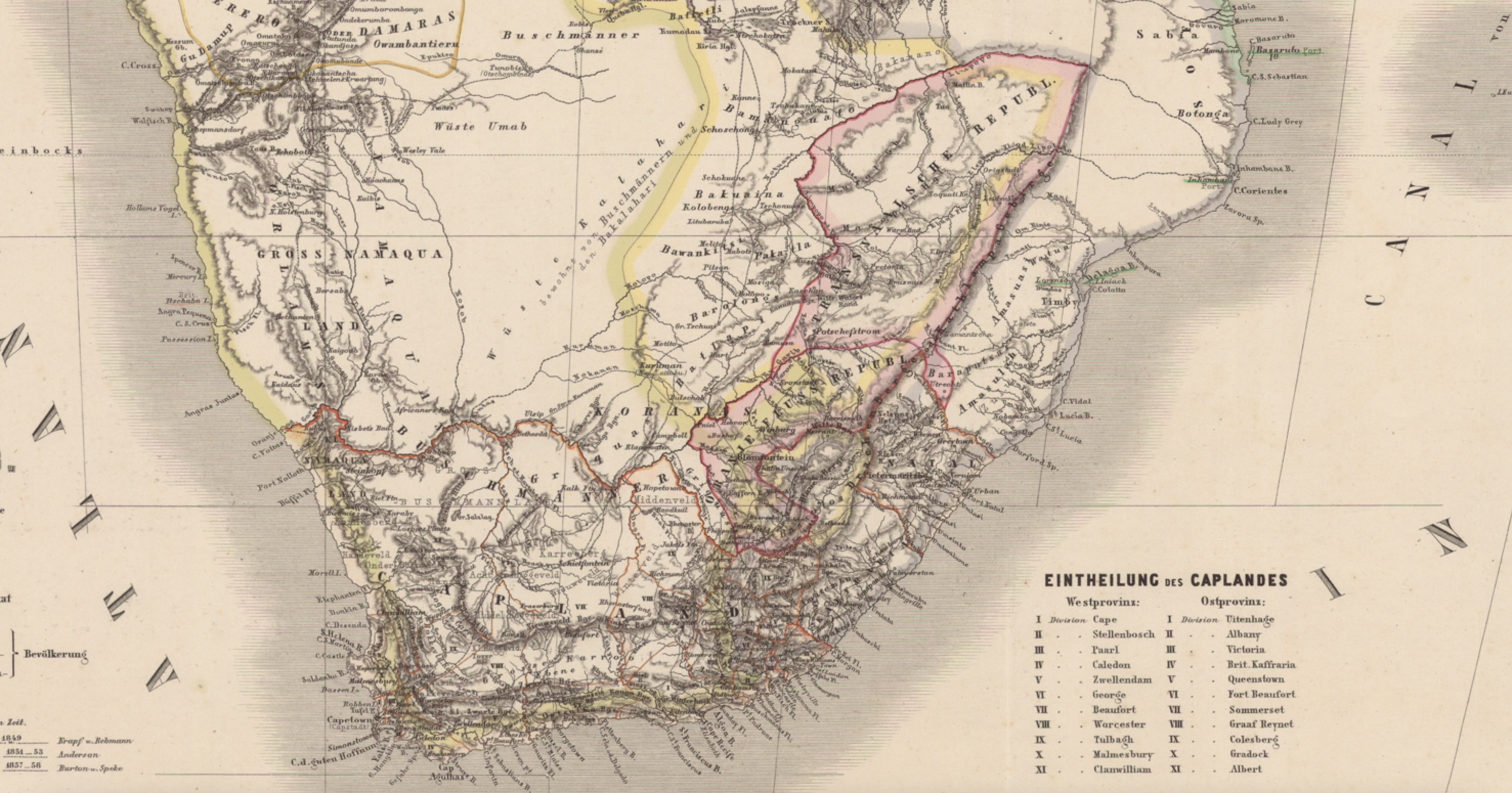

Zwangendaba Gwaza kaZiguda Jele Gumbi, commonly known as Zwangendaba, was the first king of the Ngoni and Tumbuka people of Malawi, Zambia, and Tanzania. He led his clan on an epic journey. Originally from near Pongola, his people were part of the larger Mfecane movement. Defeated by Shaka, they fled north, traveling thousands of kilometers over more than thirty years.

Migration and Expansion

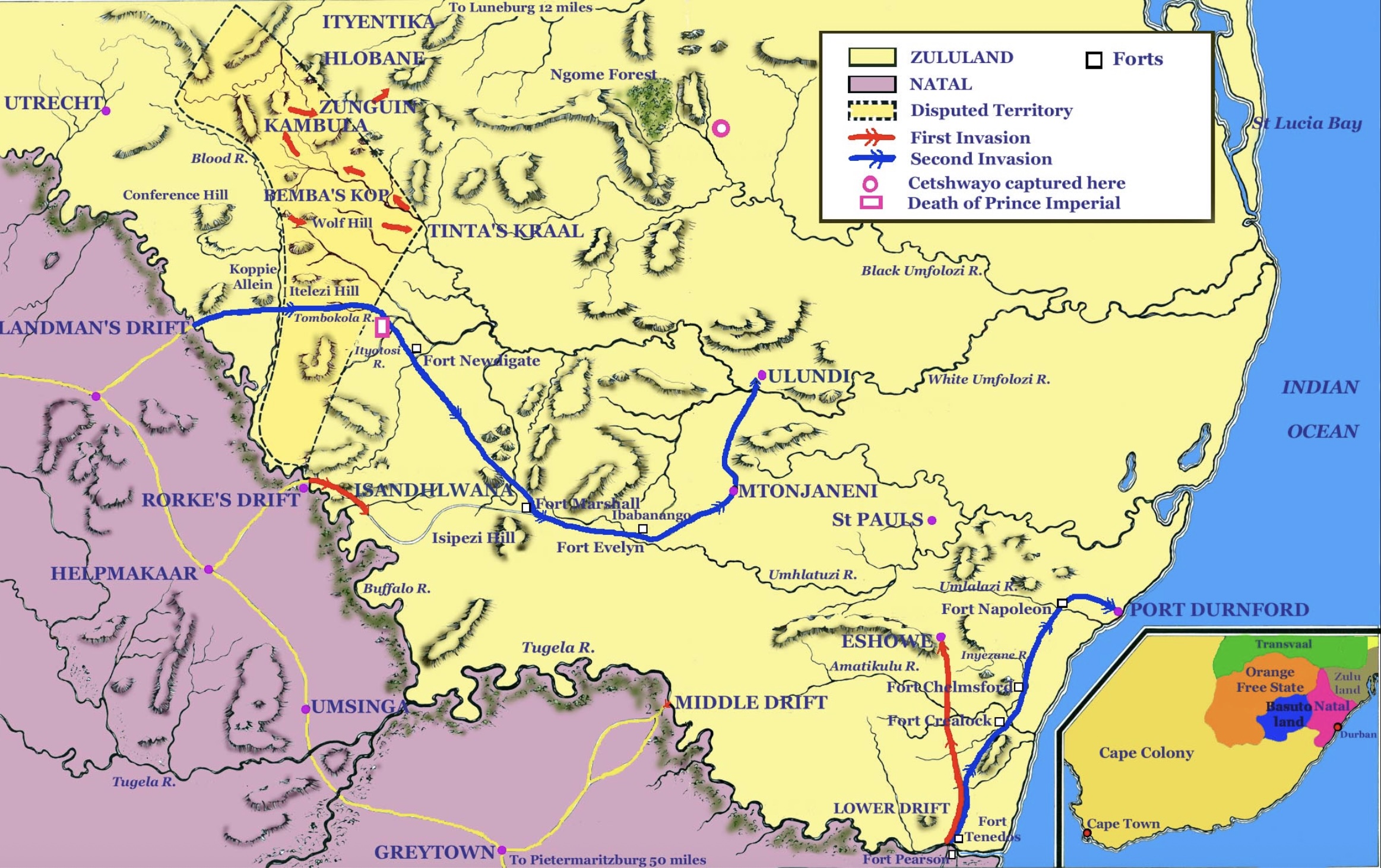

Starting in the early 1820s, Zwangendaba’s migration took his people through northern South Africa, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi, finally reaching Tanzania. This migration was not just a journey but an expansion of their dominion, particularly after crossing the Zambezi River during a solar eclipse in 1835. Oral history reports that the waters of the Zambezi parted for Zwangendaba and his people, although historians view this as a blend of myth and reality.

Warfare and Social Organization

Zwangendaba’s leadership was marked by the use of Shaka’s warfare techniques and strict social discipline. This helped unify his people and those they conquered, creating a cohesive unit. They adopted new territories and incorporated various groups, extending their influence across central Africa. This migration was a remarkable reversal of the usual narrative that the Nguni people only migrated south from their original home in central West Africa.

Succession Disputes and Family Dynamics

Upon Zwangendaba’s death in 1848, succession disputes arose. His sons from different wives, particularly from the Swazi sisters Munene and Qutu, created tensions. The tradition of polygamous marriages and the concept of “houses” complicated the succession further, leading to significant internal strife. Zwangendaba had mistakenly married Qutu instead of Munene and then married both, which led to disputes over which son was the legitimate heir.

The Role of Women

Women played crucial roles in this narrative. Lompetu, Zwangendaba’s second and most important wife, had her own kraal and wielded considerable influence. However, her childlessness and subsequent accusations of witchcraft highlighted the precarious positions women held in royal households. Lompetu was saved from execution by Gwaza Jere, who hid her and Soseya (another wife) along with her newborn son.

The Aftermath and Legacy

After Zwangendaba’s death, his people split into several groups, spreading across Malawi, Tanzania, and Zambia. The Ngoni people, originally from Zululand, left an indelible mark on central African history through their extensive migrations and complex social structures.

The Broader Historical Context

This story underscores the fluidity of human migration and the dynamic nature of African societies. The movements of the Ngoni people challenge the simplistic narratives of static communities and highlight the rich, interconnected history of the continent.

Detailed Narrative

Zwangendaba was a king of the Nguni or Mungoni people who broke away from the Ndwandwe Kingdom under King Zwide. After Zwide’s defeat by Shaka, Zwangendaba gathered his clan and fled from their home near Pongola. This dispersal was part of the Mfecane, a period of widespread chaos and warfare among indigenous ethnic communities in southern Africa during the early 19th century.

Remarkably, Zwangendaba led his people on a wandering migration of thousands of kilometers. Their journey took them through what is now northern South Africa, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi to Tanzania. The Ngoni, originally a small royal clan, extended their dominion further through present-day Tanzania, Malawi, and Zambia when they fragmented into separate groups following Zwangendaba’s death.

Zwangendaba’s Military Prowess

Using many of Shaka’s warfare methods, such as rigid discipline in military and social organization, Zwangendaba knitted his nation and the people conquered along the way into a cohesive unit. They migrated north into central Africa, a remarkable reversal of the usual storyline that the Nguni people only migrated south from their original home in central West Africa.

The migration was significant, especially as it included crossing the Zambezi River in 1835 on a day when oral history reports there was a total eclipse of the sun. The Jeje of Zwangendaba were feared and loathed because, as this group advanced north, they ravaged the countryside.

Interactions with Soshangane

Soshangane, along with his four brothers, followed the example of other Ndwandwe parties by leaving their ancestral land at Tshaneni, fleeing before Shaka. They took a route along the eastern foothills of Lubombo through Mngomezulu country to the upper Ntembe River in the first quarter of the 1820s. Soshangane lived in the Tembe area for about five years, enriching and strengthening himself through constant raids.

Between 1825 and 1827, Soshangane lived on a tributary of the Nkomati River north of Delagoa Bay. During his time there, he defeated almost all the Ronga clans in the vicinity, taking young women captive and incorporating defeated young men into his army. He stayed in the region of Delagoa Bay until 1828.

Zwangendaba’s Personal Struggles

Zwangendaba’s kraal was called Ekwendeni, and the kraal where he placed his second and most important wife, Lompetu, was called Emveyeyeni. Lompetu was an Ncumayo clanswoman and kin of Zwide kaLang, the leader of the Nxumalo line of the amaNdwandwe. After some time, Zwangendaba approached Soshangane for permission to journey north. The story goes that Soshangane gave permission but later attacked Zwangendaba’s advance party, killing or capturing many, including Zwangendaba’s first wife and son. Zwangendaba counter-attacked, recovering many captives and cattle, but the loss was significant.

During their sojourn in Zimbabwe, Zwangendaba desired to marry a Swazi girl named Munene. However, he mistakenly married her younger sister, Qutu, and later insisted on marrying Munene as well. Both bore him sons, creating disputes over succession. The people believed Qutu’s house was the senior, further complicating the succession.

The Role of Oral History

Oral historians recount that Zwangendaba once sent pots of beer from Emveyeyeni to a carousal, where a single human hair was seen floating on the froth, causing an uproar. Accusations of witchcraft led to a posse of warriors, led by Gwaza Jere, being dispatched to kill everyone at Lompetu’s home. However, Gwaza saved Lompetu and Soseya, hiding them at his home.

The Final Years

In November 1835, Zwangendaba and his adherents crossed into what is now Zambia. After a stay in the Petauke district, they moved on to the Mawiri pools in Northern Malawi and finally to the southern end of Lake Tanganyika, where Zwangendaba died in 1848.

The inevitable succession disputes ensued. After Zwangendaba’s death, there was an interregnum, and his younger brother Ntabeni was appointed interim regent. Ntabeni ordered Munene and her son Mbelwa out of the royal kraal, setting them up in a tiny hovel. This humiliation led to further conflicts and insurrections within the Ngoni people.

By 1858, the Ngoni people that Zwangendaba had led from near Pongola were broken into three major sections, widely scattered across Central Africa.

Conclusion

The story of Zwangendaba and the Ngoni people is a remarkable tale of resilience, migration, and adaptation. It challenges the simplistic narratives of static communities and highlights the rich, interconnected history of the African continent.

In our next episode, we’ll explore the happenings along the Limpopo River between 1848 and 1850.

Leave a Reply